Levitra Extra Dosage

By Y. Dan. A. T. Still University. 2018.

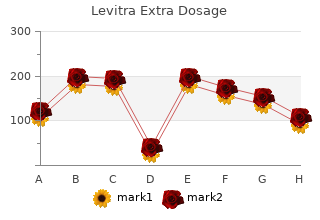

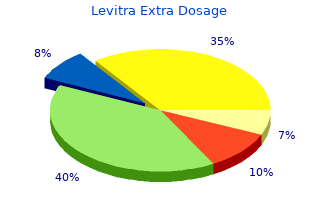

Your main practical problems may be issues such as where the changing rooms are in relation to the pool cheap levitra extra dosage 60 mg overnight delivery erectile dysfunction age statistics, and obtaining assistance to reach, and return from, the pool. There are now more and more MOBILITY AND MANAGING EVERYDAY LIFE 101 swimming pools and leisure centres offering special sessions for people who need special help, and it might be worth trying one of these sessions at first. If such sessions are not available, try lobbying your local leisure centre/swimming pool for one. It may be worth asking whether there are quiet times of the day when the pool will be freer, and assistance is more likely to be available. A small box sends electrical stimulation to muscles in the lower leg, so that you can regain useful movement. This is connected to a pressure pad in a shoe that enables the impulse to be triggered when you are walking, improving mobility. Much lower temperatures appear to be too cold, although still tolerable, whereas much higher temperatures, often found in jacuzzis or spa baths, are sometimes associated with the onset of (temporary) MS symptoms. Also, in relation to your swimming activities, if you have troublesome bladder control, it may be worth discussing this with your neurologist or GP beforehand to try and ease your concerns. Foot drop and exercise ‘Foot drop’ occurs when the muscles of the foot and ankle become weak, caused by poor nerve conduction, and either your ankle may just ‘turn over’ or, more commonly, your toes touch the ground before your heel – in contrast to the normal heel–toe action – and this might lead you to fall. One way is by exercising the relevant muscles as much as possible, through passive exercises if necessary. A special brace may be helpful, which supports the weakened ankle and allows you to walk again with the normal heel and toe action, if your leg muscles are strong enough to allow this (Figure 8. In this situation the muscles turning the foot out have weakened, and the muscles and tendons on the inside of the foot have become shortened – largely due to disuse. Thus it is vital for people with MS to try and prevent such a situation occurring by exercising the muscles controlling the ankle as much as possible. It will be important to seek some help from a 102 MANAGING YOUR MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS Figure 8. Wheelchairs and exercise Although it may sound paradoxical, it is almost more important for someone confined to a wheelchair to undertake regular exercise than someone who can walk. You should try and undertake exercises that maintain the movement and flexibility in your joints as much as possible – through the ‘range of motion’ and stretching exercises described earlier. As far as possible, try and maintain also your upper body strength – this is particularly important for good posture, which itself will help prevent some of the more problematic aspects of being in a wheelchair for a long time. If possible, it is very helpful just to stand for a few minutes each day, with the help of someone else or with an increasing range of equipment now available for this purpose. It is known that bone density tends to decrease (causing ‘osteoporosis’) more quickly if weight is not borne by the legs and feet on a regular basis and low bone density is also one of the contributory factors of fractures. This is another reason why standing should, if possible, be undertaken – even if only for a very short period. As with sitting in a chair, you ought to learn specific exercises to be able to shift your weight on a regular basis, to prevent skin breakdown at the points where your body is in contact with the wheelchair, and ultimately to prevent pressure sores. Basically, as the name suggests, they arise when the skin begins to break down from too much continuous pressure, from a chair or bed, for example, on key points of your body. Once this pressure has been applied for a long time, blood circulation to the area lessens or ceases, the tissues get starved of oxygen, and the skin and related tissues break down. Such pressure sores are particularly dangerous because, left untreated, they can lead to infection of the underlying bare tissue or to blood infection (‘septicaemia’), which can threaten your life. Most people do not get pressure sores because they move very frequently and thus pressure is never exerted on one point of their body for long enough for a pressure Figure 8. Danger areas are the lower back, the shoulder blades, the insides of knees, hips, elbows, ankles, heels, toes, wrists, and even sometimes ears (Figure 8. Pressure sores are more likely if you are in a wheelchair, or are sitting or in bed for long periods of time. Initially, a pressure sore may just look like an area of reddened skin, or even a small bruise.

Early research focused on couple interventions to improve disease man- agement purchase 40mg levitra extra dosage free shipping erectile dysfunction treatment by acupuncture, medical compliance, quality of life, and mortality for patients with chronic illness. In another controlled study (Taylor, Bandura, Ewart, Miller, & De- Busk, 1985), wives of heart attack patients were asked either to observe their spouse take a treadmill stress test or to take the test with their spouse, three weeks after the heart attack. Wives who walked the treadmill and directly experienced what their husbands were capable of were significantly more confident and less anxious about their husbands’ health and capability than the wives who only observed the test. They were also less overprotective of their husbands, which may relate to the finding that their husbands showed improved cardiac functioning at 11 and 26 weeks after the heart attack. Managing Emotional Reactivity in Couples Facing Illness 255 Although there is a significant body of clinical literature that addresses psychotherapy with families facing illness (see McDaniel, Hepworth, & Doherty, 1992), literature that focuses on helping couples in particular is still relatively scarce—usually found either in textbooks on couples therapy with illness treated as a special issue (e. A wide variety of specific approaches have been offered on the subject of couples and illness, including behavioral (Schmaling & Sher, 2000), existen- tial (Lantz, 1996), and interpersonal (Lyons, Sullivan, Ritvo, & Coyne, 1995). Many of these approaches delineate key issues that couples must con- front when illness strikes and offer strategies, drawn from their particular theoretical framework, to help couples negotiate these issues. Rolland (1994) addresses the impact of illness on intimacy in the couple relationship, focusing in particular on the need for the therapist to assist the couple in addressing the relationship imbalances (skews) that can emerge as a result of illness in one member. Differences in ability that de- rive from the health status of each member of the couple can translate into differences in power and control between them, leading to tension, re- sentment, guilt, distance, and discouragement. Rolland recommends that the couple redefine the illness as "our" problem, rather than "your" or "my" problem, and work as partners to manage the challenges they both face as a result of the illness. Rolland also suggests that therapists as- sist the couple to resist the tendency of illness to dominate the family identity by drawing a boundary around the illness. This can be done by, for example, establishing protected time in which illness talk is off limits as well as by maintaining their pre-illness family and social routines as much as possible. Kowal, Johnson, & Lee (2003) have applied the tenets of Emotionally Focused Therapy (EFT) to working with couples and illness; EFT is an in- tegration of experiential and systemic approaches to therapy that under- stands couple conflict as relating to behaviors and emotions that express underlying attachment needs. They argue that since attachment style has been shown to be related to the onset and exacerbation of chronic illness as well as to a variety of health-related behaviors, then addressing attach- ment needs and the emotions they generate by use of EFT is a promising avenue for assisting couples dealing with chronic illness. They go on to note that "the goals of EFT in working with chronic illness in couples are to normalize and validate each partner’s experience, to help partners process their emotional experiences, to externalize negative interaction 256 SPECIAL ISSUES FACED BY COUPLES cycles, and to help partners seek safety, security, and comfort from each other (i. COUPLES AND ILLNESS—STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM Factors that influence how illness affects a couple include the nature and severity of the illness; individual variables such as age, gender, ethnicity, general coping style, and previous experience with illness; and relation- ship variables such as degree of conflict, stability, and trust, communica- tion and problem-solving styles, and relationship satisfaction. Issues facing couples dealing with illness include loss—of ability, of a sense of normalcy, of expectations for the future, and possibly loss of life; identity changes precipitated by the presence of the illness; relationship imbalances deriv- ing from the loss of function in the ill spouse; the need to communicate about difficult subjects; establishing the meaning of the illness; the legacy of transgenerational family experiences with illness, vulnerability, and loss; gender issues; caregiver burden and burnout; and the ill spouse’s feel- ings of guilt and uselessness. Literature about helping couples deal with the impact of illness gener- ally addresses the emotional and pragmatic impact of illness on the couple relationship, including loss of function and identity, reassignment of roles, learning to communicate about difficult issues, and so on. What has re- ceived less attention is how to understand and address complicated emo- tional reactions to illness—reactions that seem to go beyond what would be expected, even given the extremely difficult nature of the challenges that illness can present. For some couples, illness presents an opportunity to put things in per- spective, resulting in increased intimacy and relationship satisfaction in the face of challenge. For other couples, the challenge of illness may derail previously adequate coping mechanisms and plunge a formerly stable rela- tionship into a terrifying tailspin. A strain of serious illness can exacerbate prior relationship difficulties and accelerate the deterioration of a couple relationship. The emotional processes underlying such problematic reac- tions to the difficult challenges of illness are rooted in the premorbid levels of functioning in each spouse and in the couple relationship. Bowen family systems concepts (Bowen, 1985)—especially emotional reactivity and dif- ferentiation—offer a way to understand how to assess and assist couples experiencing particularly problematic reactions to physical illness. BACKGROUND AND KEY PRINCIPLES OF THE APPROACH—MEDICAL FAMILY THERAPY Medical family therapy is a metaframework for psychotherapy; it provides overarching principles within which any form of psychotherapy can be Managing Emotional Reactivity in Couples Facing Illness 257 practiced (McDaniel et al. Medical family therapy is based on a biopsychosocial systems theory (Engel, 1980; McDaniel et al. This theory, unlike traditional biotechnical medicine, is expressly systemic and sensitive to the effects on health and illness of context, including such vari- ables as gender, race, culture, and class. The goals of medical family therapy are to optimize agency and communion for the patient, the family, and the health professionals involved (Bakan, 1966). Communion refers to a sense of connection—with family, friends, health professionals, community, and spiritual communionity. Taken together, agency and communion are the foundations of individual effectiveness within a relational context.

This equipment allows multiplanar levitra extra dosage 40 mg visa erectile dysfunction drug therapy, real-time visualization for cannula introduction and cement injection and permits rapid al- ternation between imaging planes without complex equipment moves or projection realignment (Figure 14. However, this type of radio- graphic equipment is expensive and is not commonly available in in- terventional suites or operative rooms unless it is used for neurointer- ventional procedures. It takes longer to acquire two-plane guidance and monitoring infor- mation with a single-plane than with a biplane system. However, it is feasible and safe to use a single-plane fluoroscopic system as long as the operating physician recognizes the necessity of orthogonal projec- tion visualization during the PV to ensure safety. With a single-plane system for PV, these C-arm moves will mean a slower procedure than that offered by a biplane system. This method gained a brief period of popu- larity in the United States with the study published of Barr et al. Although the contrast res- olution with CT is superior to that of fluoroscopy, with CT one gives up the ability to monitor needle placement and cement injection in real time. Even so, CT may be acceptable for needle placement, particularly if a small-gauge guide needle is first placed to ensure accurate and safe location before a large-bore bone biopsy system is introduced. CT does not afford one the opportunity to watch the cement as it is being injected or to alter the injection volume in real time if a leak occurs. Also, unless a large sec- tion is scanned with each observation, if leaks occur outside the scan plane, they may be missed if one is looking only locally in the middle of the injected body. The ability to perform fluoroscopy in two pro- jections without having to move equipment greatly speeds and simplifies vertebroplasty. For all these reasons, CT has not found a primary role in image guidance for PV; it is reserved for ex- tremely difficult cases. Laboratory Evaluations Coagulation tests results should be normal, and the patient should not be taking Coumadin. Coumadin may be discontinued and replaced with enoxaparin sodium (Lovenox; Rhône-Poulenc Rorer Pharmaceu- ticals, Inc. Coumadin may also be stopped and replaced with heparin, but this medication must be administered intravenously, requiring hos- pital admission. Both enoxaparin sodium and heparin can be reversed with protamine sulfate before PV and restarted postoperatively. PV is not recommended for patients with signs of active infection, but elevated white blood cell counts clearly associated with medical conditions such as myeloma or secondary to steroid use are not con- traindications. As mentioned earlier, antibiotics are added to the cement itself only in the situation of immunocompromise. Anesthesia During PV, it is common to use both local anesthetics and conscious sedation to make the patient comfortable and relaxed. Patients who re- quest not to receive intravenous sedation or cannot have it for safety reasons still can be treated with only mild discomfort if appropriate attention is given to local anesthetic placement. To reduce the sting and discomfort associated with locally administered anesthetics (lidocaine, etc. I commonly use a mixture that includes both bicarbonate and Ringer’s lactate (Table 14. At my institution, this mixture is prepared daily for all procedures requiring local anes- thetics. Whatever the chosen local anesthetic preparation, the skin, subcuta- neous tissues along the expected needle tract, and periosteum of the bone at the bone entry site must be thoroughly infiltrated. When this has been accomplished, the patient will experience only mild discom- fort while the bone needle is being placed, regardless of whether con- scious sedation is used. Conscious sedation has become a common adjunctive method of pain and anxiety control in awake patients who undergo minimally TABLE 14. Modified local anesthetic solutions Amount (mL) Lactated Solutiona Lidocaine (4%) Ringer’s Bicarbonate Epinephrine 1 2 4 24 2 0. I use a combination of intravenous midazolam (Versed, Roche; Manati, PR) and fentanyl (Sublimase, Abbott Labs; Chicago). To decrease anxiety and diminish the discomfort associ- ated with positioning, it may be helpful to begin these medications before the patient is placed on the operating table. The final amount is determined with titration while observing the patient’s response. General anesthesia is rarely needed for PV, but it is used occasion- ally for patients in extreme pain who cannot tolerate the prone posi- tion used in PV or for patients with psychological restrictions that pre- clude a conscious procedure.

Gilligan (1982) and Erikson (1968) suggest that in gaining a sense of themselves generic 40 mg levitra extra dosage with visa erectile dysfunction lubricant, young women rely more on interpersonal relationships than do young men, thus women who were abused by someone of a close famil- ial nature may have difficulties developing a healthy self-identity. In either case, however, a focus on male survivors and their partners is beyond the scope of this chapter. Because most perpetrators of sexual abuse are likely to be men, the impact of having been sexually abused on a later ro- mantic relationship is different when the partner is female (as in a lesbian relationship) than when the partner is male. However, to limit the scope of issues to be considered in this chapter, we focus exclusively on heterosex- ual relationships. Prior to discussing how couples therapists might proceed in treating a couple such as Maria Elena and Jose, and before meeting other couples with similar histories, this chapter includes an overview of the impact and nature of sexual abuse and considers the experience of the sexual abuse survivor’s partner. We next discuss assessment issues looking at the case of Maria Elena and Jose in more detail. We conclude the chapter with the cases of Sharon and Luke, and Glenda and James, illustrating key issues in the treatment of these couples. NATURE AND IMPACT OF SEXUAL ABUSE Sexual abuse by a family member or by someone outside of the family may involve a child or adolescent. This abuse can include a variety of forms of sexual violations ranging from fondling, to sexual intercourse, to more un- usual forms of sexual behavior. The form of the sexual abuse, how long it 274 SPECIAL ISSUES FACED BY COUPLES lasted, whether it encompassed a single violation or multiple violations, whether there was a single or multiple perpetrators, the nature of the relationship between perpetrator and victim (e. Females are more likely to be abused by a family member (Finkelhor, Hotaling, Lewis, & Smith, 1990), and those sexually abused by a father figure exhibit the most long-lasting effects and the worst adjustment outcomes (Finkelhor, 1979; Herman, Russell, & Trocki, 1986; Russell, 1986; Tsai, Feldman-Summers, & Edgar, 1979). Briere (1992), in describing the long-term impacts of child abuse, indi- cates that these reflect "(a) the impacts of initial reactions and abuse- related accommodations on the individual’s later psychological develop- ment and (b) the survivor’s ongoing coping responses to abuse-related dys- phoria" (p. Of particular interest here, will be the way in which those individual reactions in turn impact the couple relationship. Recent thinking suggests that experiencing sexual abuse (or any type of trauma) may actually impact the biological processes of brain development. Further, early severe trauma may give rise to "a form of divided attention (such as entering a state of intense imagination or trance)" and explicit (conscious) memory for the trauma may be impaired. Implicit (unconscious) memory may encode the more frightening aspects of the trauma that can later be "automatically reacti- vated, intruding on the traumatized individual’s internal experience and external behaviors without the person’s conscious sense of recollection or knowledge of the source of these intrusions" (pp. Memories are biologi- cally encoded then stored, and when repeatedly active at the same time be- come associated so that they facilitate each other. The varieties of symptomology displayed by survivors of childhood sex- ual abuse are impressive. Stein, Golding, Siegel, Burnam, and Sorensen’s (1988) study of more than 3,000 Los Angeles adults, identified a subgroup that had been sexually abused as children and studied the lifetime preva- lence of emotional reactions. Seventy six percent of those abused developed some type of symptom, with 83% of women and 66% of men becoming symptomatic. Eighty-six percent of Hispanics and 73% of non-Hispanic whites, respectively, developed some symptom. For the group as a whole, 50% developed symptoms of anxiety, 48% had difficulty with anger, 48% felt guilty, 45% were depressed. Thirty three percent were fearful, and 24% to 28% experienced behavioral restrictions, diminished sexual interest, fear Treating Couples with Sexual Abuse Issues 275 of sex, diminished sexual pleasure or insomnia. Among women, the above symptoms were experienced by as many as 10% more participants in each category. The type of symptoms described in the above-cited study are con- sistent with those reported by others (for example, Briere & Conte, 1993; Browne & Finkelhor, 1986; Chu & Dill, 1990; D. In regard to symptoms that manifest themselves in the sexual arena, Becker, Skinner, Gene, Axelrod, and Cichon (1984) suggest that the survivor’s inhibition of sexual feelings leads to avoidance behavior and allows the negative attitude toward sex to endure. While the fear or avoidance of sex may exist for women with a history of sexual abuse, women survivors may also present with histories of high-risk sex, promiscuity, and prostitution (Maltz, 2002) in an effort to resolve intrapsychic conflicts (Scharff & Scharff, 1994), fac- tors that may further confound their sense of self and sexuality and impact their relationships with a spouse or partner. Browne and Finkelhor (1986) conclude that about 20% of adults who were sexually abused as children ev- idence serious psychopathology as adults. Other researchers (Kessler, Abel- son, & Zhao, 1998) found that lifetime depression for women survivors of sexual abuse was 39. The incidence of any mood, anxiety, or substance disorder was 78% com- pared to 48. Briere, Cotman, Har- ris, and Smiljanich (1992) indicate that intrusive, avoidant, and arousal symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are experienced by both clinical and nonclinical groups of individuals who experienced childhood sexual abuse.

9 of 10 - Review by Y. Dan

Votes: 306 votes

Total customer reviews: 306